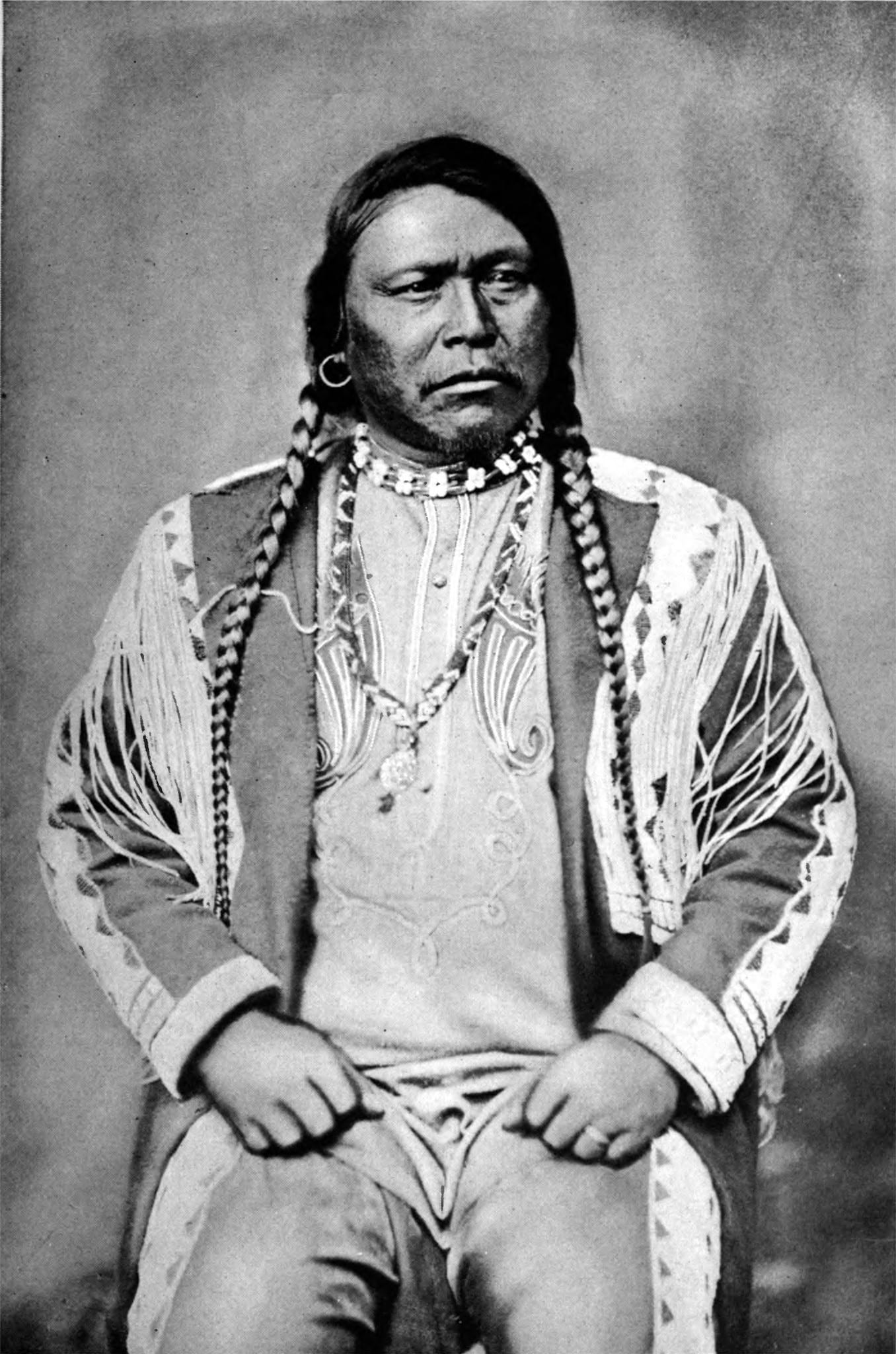

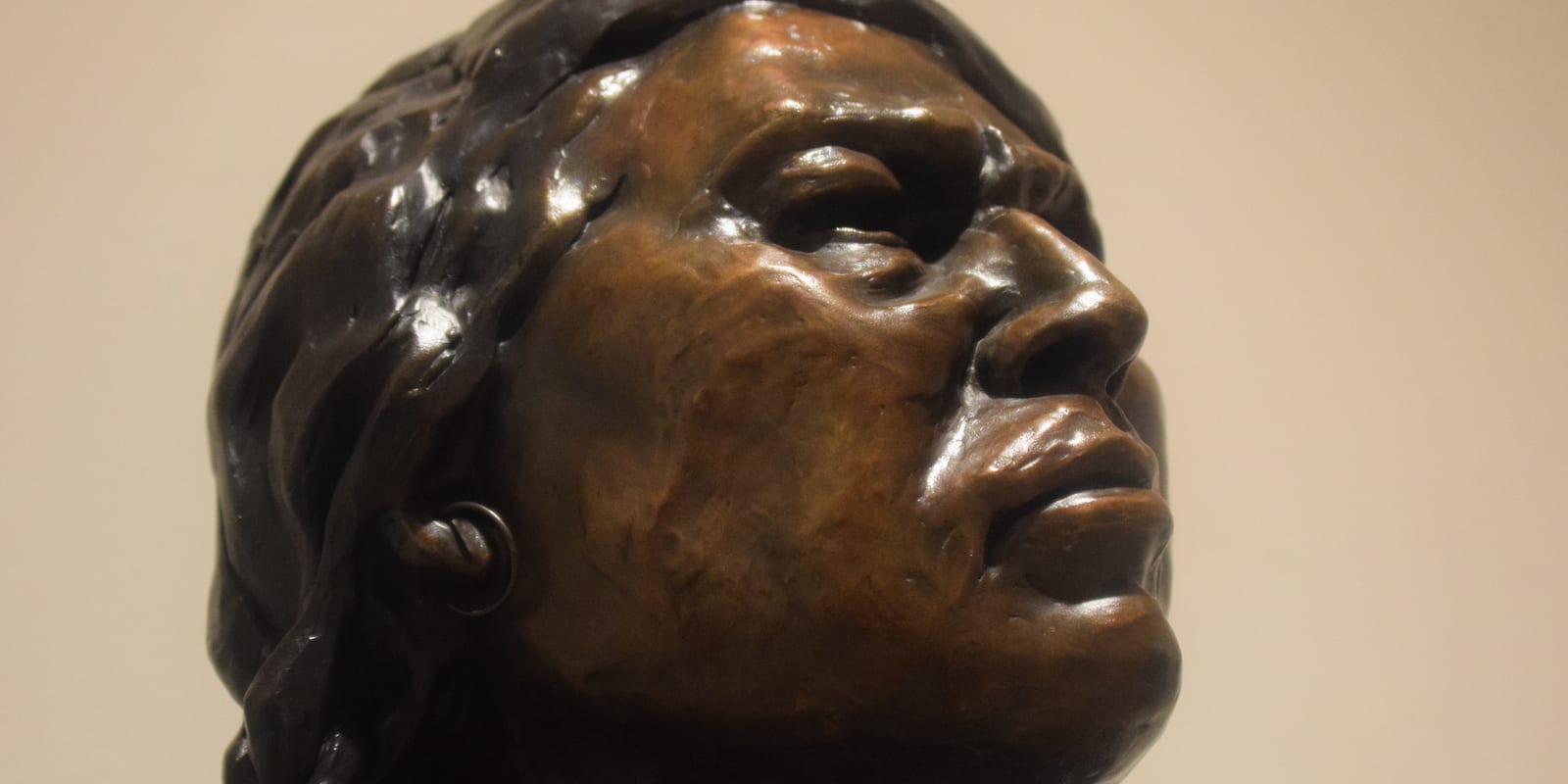

Historians remain divided on whether Chief Ouray’s well-intentioned actions ultimately hurt or helped the Ute people who lived in Colorado thousands of years before it became an American state.

But most are in agreement about two things: the long-term impacts of his actions for Ute peoples in Colorado and beyond, and his uncompromising desire to seek out peaceful solutions no matter how high the cost, grave the threat, or challenging the circumstance.

A Colorado town and county are both named after this complex and influential Ute leader, whose storied life was filled with true, larger-than-life events that would fit seamlessly into a captivating work of fiction.

Ouray, whose name translates to”Arrow” in the Ute language, was born in Abiquiú, New Mexico, in 1833. The son of a Jicarilla Apache father and a Tabeguache Ute mother, as children, Ouray and his brother were sent to the town of Taos to work as indentured servants for the Martínez family, which was the largest and most powerful landowner in the region at the time.

While serving the family, Ouray put his intelligence and intuition to use learning about local hierarchical power structures, business, and culture. The knowledge he obtained as a child servant would inevitably help him become a skilled and influential leader later on in life.

On the cusp of adulthood in 1850, Ouray returned to his birthplace to work for relatives of the Martínez family before moving to Colorado. In his twenties, Ouray is said to have picked up Spanish, Ute, and some English in addition to the Apache dialect he already spoke.

Ouray Marries Chipeta

Alongside his unique understanding of regional power structures and access to high-profile figures, this linguistic advantage would eventually elevate his position in society to someone knowledgeable, trusted, and widely respected. In 1859, two years after the birth of his first son and the sudden death of his first wife, Ouray married a considerably younger woman named Chipeta.

Remarkably beautiful and a skilled negotiator, Chipeta became a beloved and well-known figure in her own right. Historians believe that Ouray’s son was captured by the Lakota tribe in 1862, but what happened to him after the capture remains a subject of debate.

Treaty at Conejos

In the fall of the following year, Ouray’s long and important relationship with the US Government began with his work on completing the Treaty at Conejos, a Ute community in the San Luis Valley. Ouray acted as a representative of the Tabeguache people and a prominent signer of a hugely significant treaty for the Utes and other Indigenous peoples in the region.

The treaty relinquished all Ute land east of the Continental Divide as well as Middle Park to the US. The land is said to have already been occupied by white settlers, but the treaty made their occupation legally recognized. The US Congress affirmed the treaty the following year, and payments to the Ute people were arranged. The agreement caused the forced removal of countless Utes from their ancestral homes.

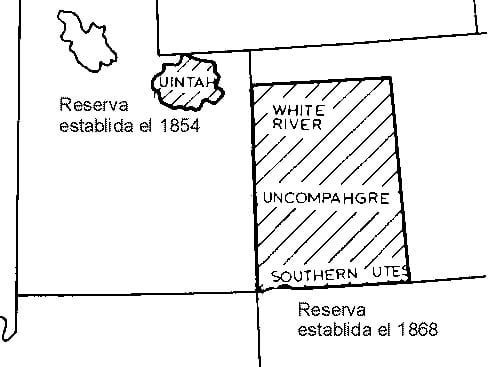

The Treaty of 1868

In 1868, Ouray became part of negotiations for another treaty with similarly profound impacts on the Ute people. This one involved the removal of Utes living in the San Luis Valley and the creation of a large reservation located on the Western Slope for all Utes living in the Colorado Territory (Colorado wouldn’t become an official US state until 1876).

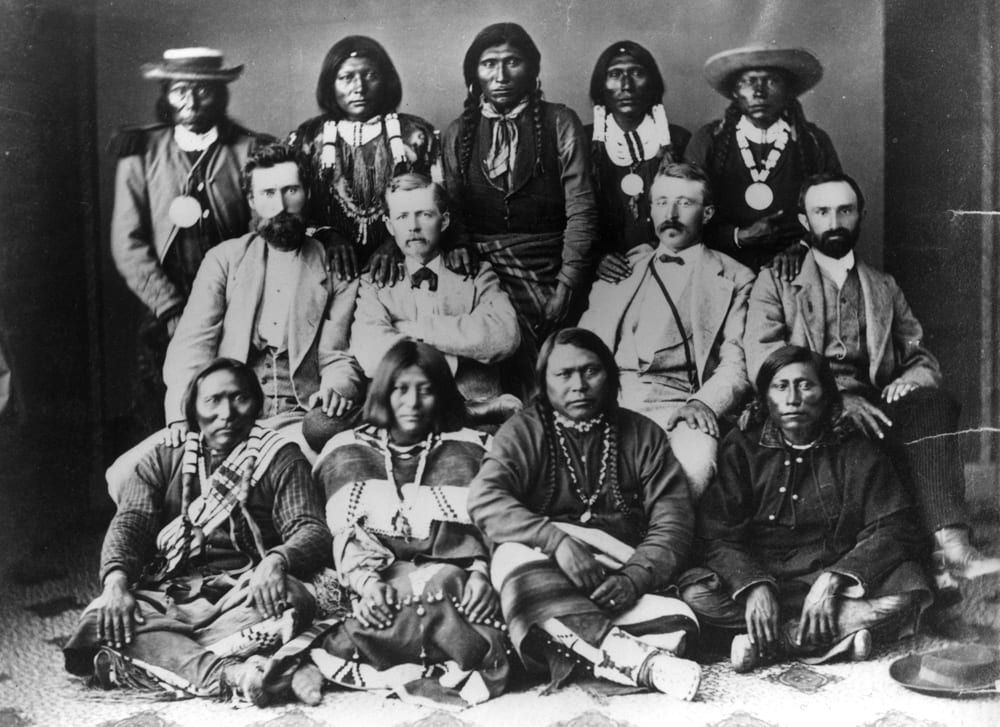

A broader range of Ute leaders attended meetings to discuss this treaty than the one at Conejos, but the decisions made there didn’t represent the wishes and interests of all Ute people. Along with seven Ute representatives, famed US Army officer and frontiersman Kit Carson, Commissioner of Indian Affairs Nathaniel G. Taylor, and others met in Washington D.C. to draft the treaty. At the meeting, Ouray was officially named Chief of all Ute peoples.

The newly formed Ute reservation comprised 20 million acres, and the U.S. government quickly met again with Ouray to obtain more Ute land. Prospectors trespassing on remaining Ute lands found gold and silver deposits there and refused to leave. Rather than adhering to their agreement, Government officials began attempts at acquiring the land for mining interests.

Brunot Agreement

When Ouray and other Ute leaders refused to sell more of their land, chairman of the Board of Indian Commissioners Felix R. Brunot told him he could reunite him with his captured son, and Ouray was eventually persuaded to give up a mineral-rich four-million-acre piece of land in exchange for a yearly payment to the Utes and hunting rights.

The US had formally declared that it would no longer recognize the sovereignty of Indian Nations in 1871, which made this negotiation an “agreement” rather than a treaty. An annual $1,000 payment for Ouray and Chipeta was also a part of what’s now known as the Brunot Agreement.

The Meeker Incident

By the end of the decade, it was clear that the Ute people didn’t care for life on their reservation, and in 1879, Ouray was forced to mediate a violent dispute between the Utes he represented and white settlers. The local Government-appointed Indian Agent Nathan C. Meeker was known for his attempts to force Utes out of their way of life and into Christianity and farming, attempts that failed every time.

After Federal troops arrived in the area to guard his agency, some Utes felt threatened and responded by killing Meeker and holding his family hostage. Today, historians place blame for the violence on Meeker, but at the time, the event inspired white Coloradans to call for the complete removal of Ute peoples from the state.

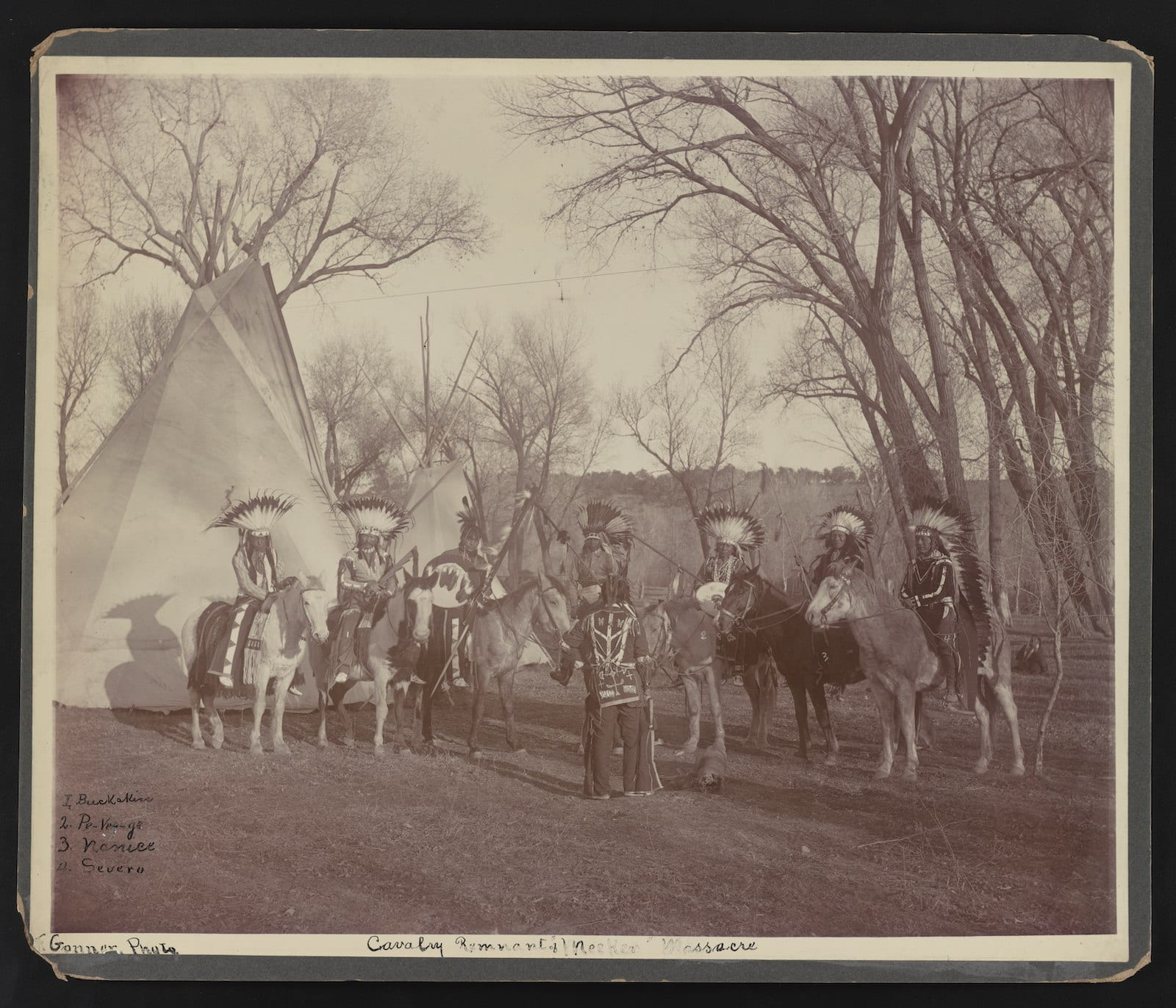

Relocation to Northern Utah

Fearing retaliatory violence and the death of his people, Ouray eventually agreed to a plan to move the Uncompahgre Utes to a permanent reservation in northern Utah in 1880. Few initially agreed to relocate, and as pressure mounted for them to leave, Ouray believed he was tasked with saving the Utes from destruction.

On a trip to southwestern Colorado to convince a Ute leader there to sign on to a new peace agreement, Ouray died of a kidney disorder he’d been suffering from for five years. While Utes in southern Colorado were eventually allowed to stay, the Uncompahgre Ute peoples were forced by a 1,000-strong band of US troops to make a 350-mile journey west on foot to the reservation named after their late Chief. Chipeta lived in near poverty until the age of 81 and was never fully paid what she was owed by the US Government.

While many in positions of power use their roles to make life better for themselves, historians describe Ouray as a complex figure who reluctantly represented the Ute people and was often placed in the impossible position of trying to pacify Government officials and protect the lives of his people at the same time.

Historians and modern Ute peoples are divided as to whether Ouray should take the blame for the forced removal of Colorado’s northern Utes, but his defenders believe his actions were always aimed at peace and that he may have saved his people from death or even genocide.

Top Things To Do In Steamboat Springs, Colorado

Top Things To Do In Steamboat Springs, Colorado