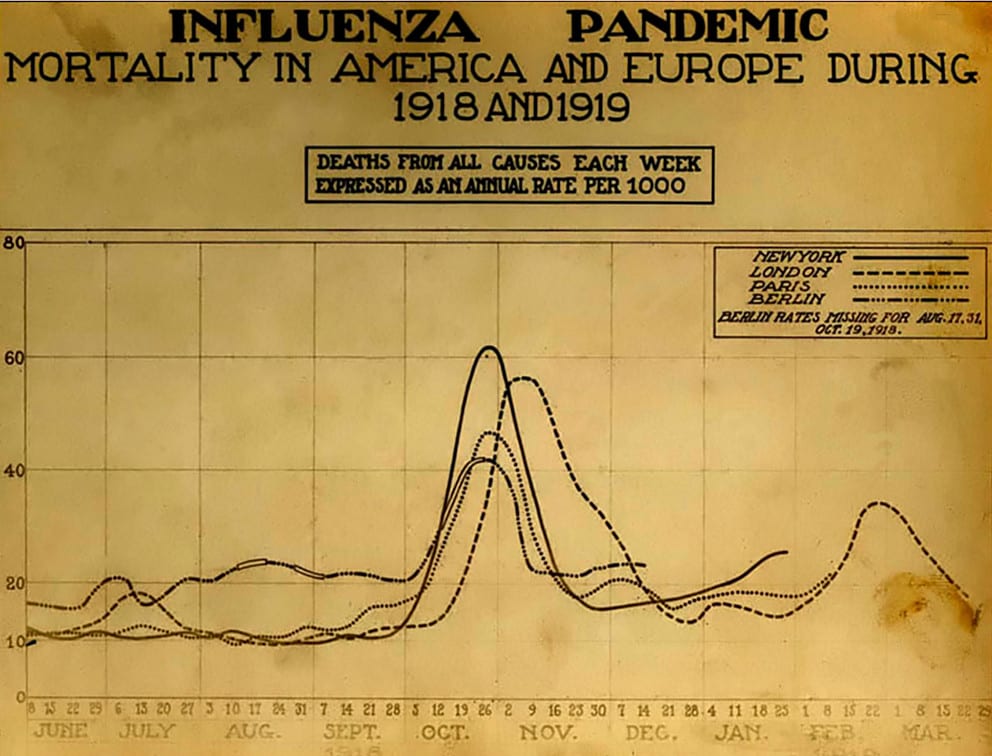

An unfortunate set of circumstances made what the CDC today calls the “1918 Pandemic Influenza” uniquely lethal and widespread. The First World War claimed 17 million lives, but the pandemic that directly followed amassed an astounding death toll of 50 million around the world, and some estimates tally the number of dead up to 100 million.

Experts believe that 40-50% of the world’s population was infected by the Spanish Flu, and the sickness indiscriminately struck the powerful and poor alike. Walt Disney and US President Woodrow Wilson survived deadly influenza while acting First Lady Rose Cleveland and many influential politicians, artists, and athletes did not.

1918-1919 Pandemic Influenza

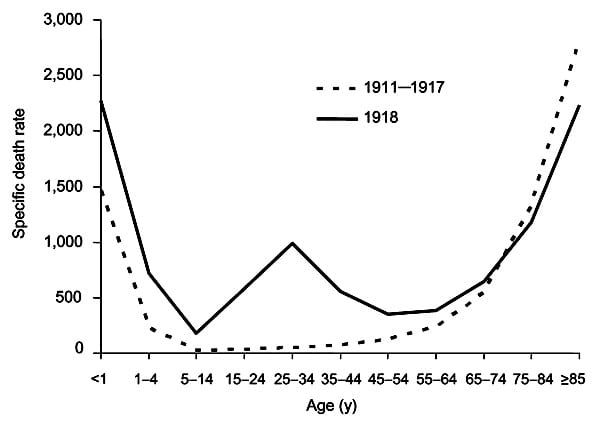

Typical influenzas pose the greatest risk to young children and those aged 65 and over, but the pandemic flu that ravaged the world between 1918-1919 killed millions between the ages of 20-40, and most of the lives lost were young and healthy.

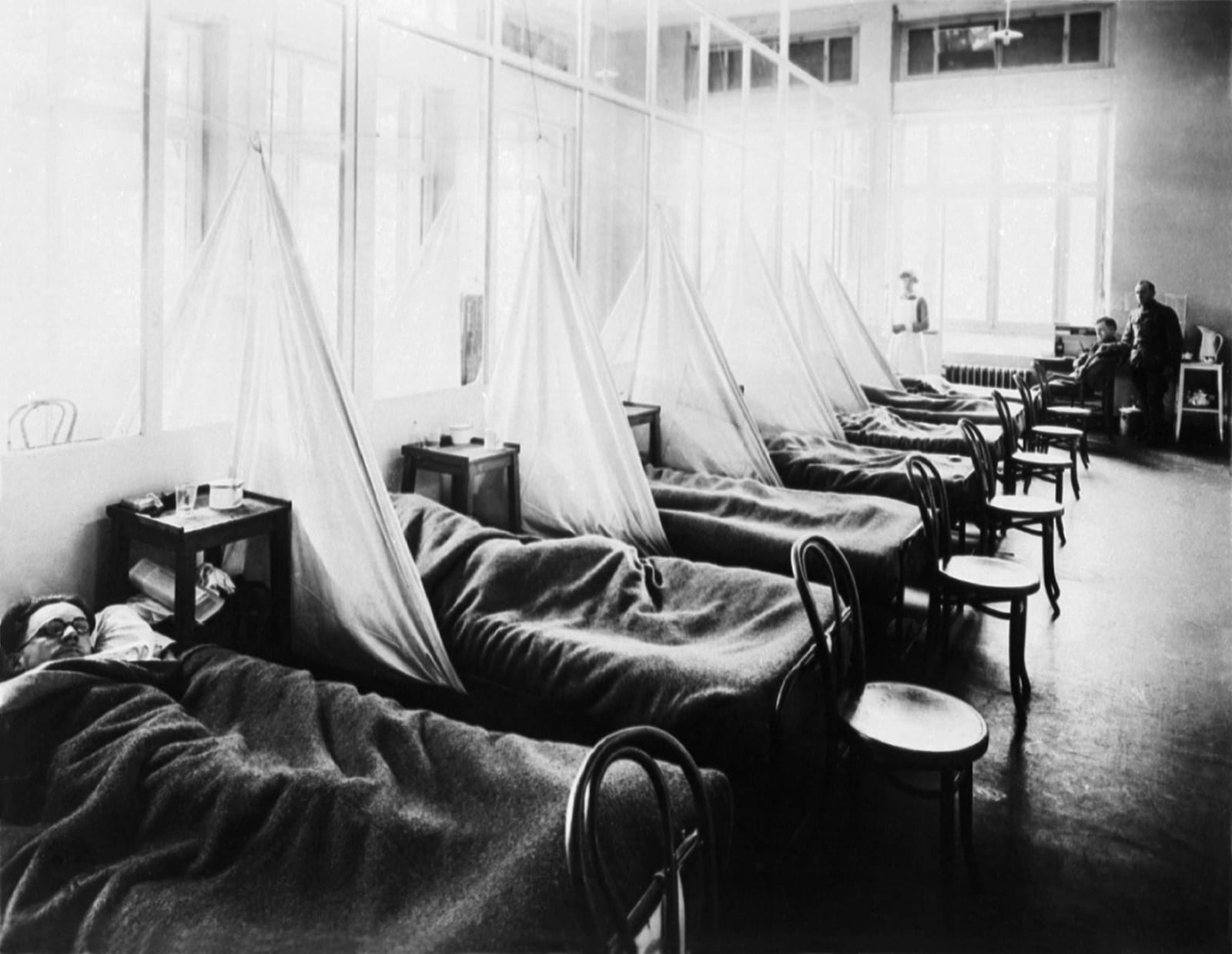

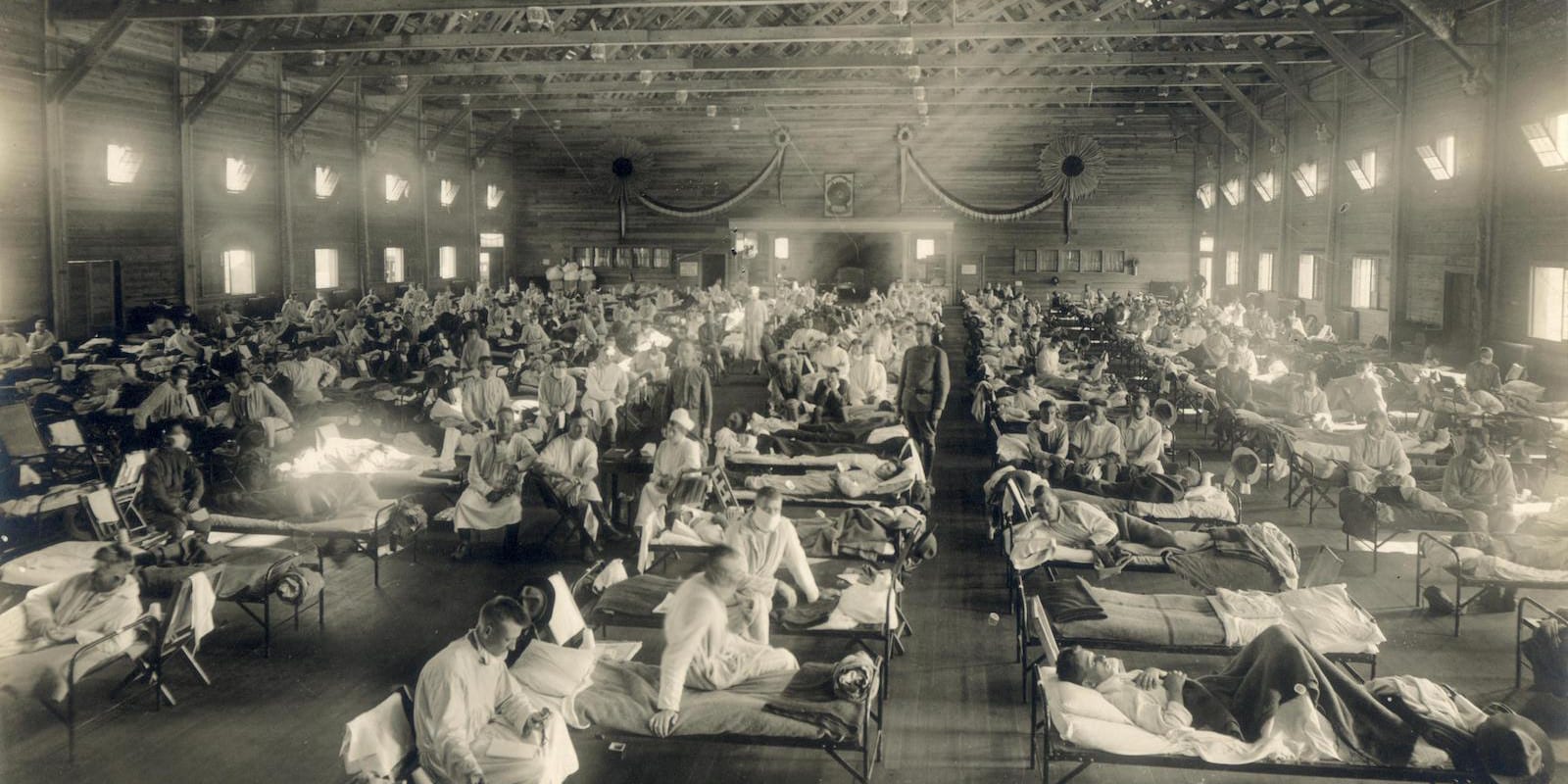

At the peak of influenza’s devastating second wave that swept through America in the fall of 1918, many victims perished within hours of experiencing symptoms, which included skin turning a haunting blue color and lungs rapidly filling with fluid.

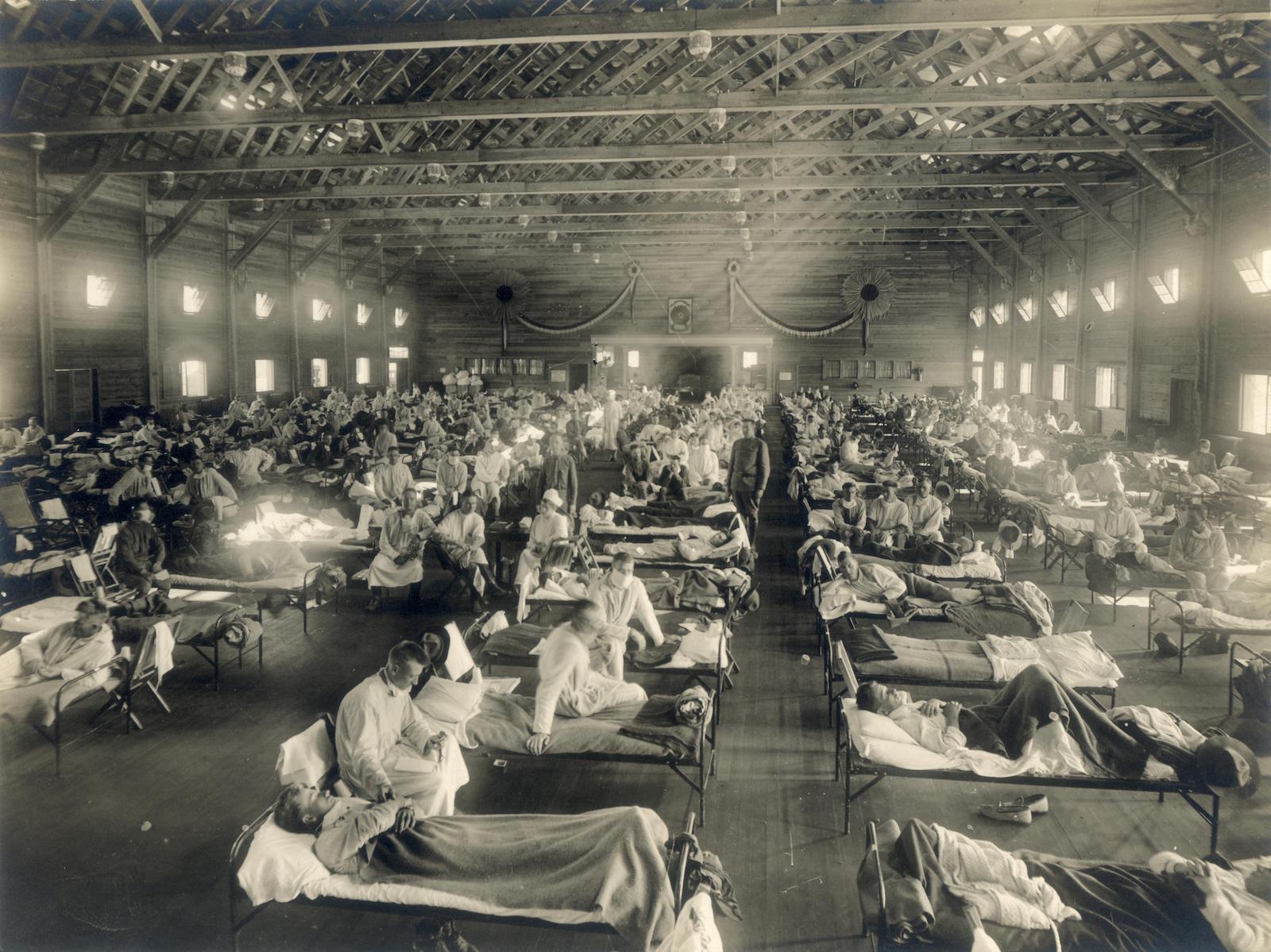

The death toll in America was so immense that life expectancy fell by a staggering 12 years. As WW1 wound down, the virus was able to spread rapidly and easily to every corner of the globe through the close quarters of military barracks and on transport ships. More than a century later, experts still don’t know why so many young, healthy adults succumbed during the epidemic.

The term “Spanish Flu” is a misnomer. While many still inaccurately assume the deadly virus originated in Spain, the pandemic got its name because, unlike many countries, Spain’s media openly reported on the disease in terrifying detail. Much of the world experienced heavy censorship of the news during the war, and many countries first learned of the virus from Spanish news sources because the country was neutral. Inside Spain, some believed the flu came from nearby France and dubbed it the “French Flu.”

The Spanish Flu in Colorado

While historians and scientists still haven’t formed a consensus as to where the virus first emerged, many believe its origins lead back to a military base in Haskell County in Kansas, where news of the flu’s first 18 severe cases and three deaths were first reported in the spring of 1918. Haskell County is 63 miles from the Colorado border. However, the state’s proximity to the first known cases of Spanish flu didn’t mean the state was exposed early.

Like much of the United States, Colorado’s first recorded cases of the flu occurred in early fall, during the virus’ devastating second wave. The first known cases of the Spanish Flu in Colorado were 12 young military trainees who came down with the deadly strain on September 21, 1918, at the University of Colorado in Boulder. The virus spread rapidly throughout the state throughout the following fall and spring.

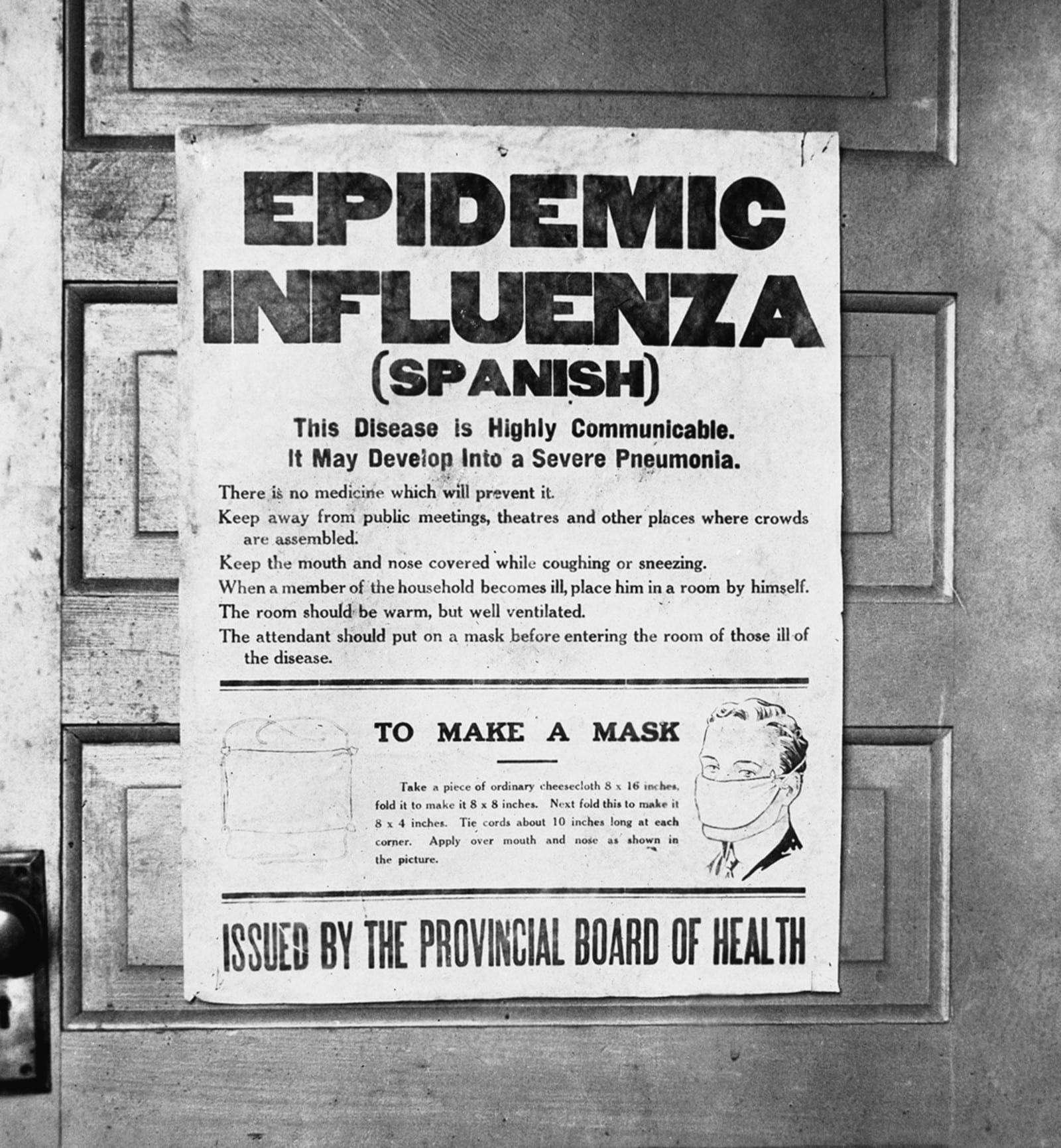

The first death reported in Denver was a Denver University student who’d just returned from Chicago. In Denver and beyond, leaders reacted slowly to the impending threat, and many today believe Colorado’s actions weren’t nearly strict or consistent enough to be effective. Former Denver mayor and City Manager of Health and Charity Dr. William H. Sharpley wisely advised residents not to crowd and to cover their sneezes, but also curiously recommended that people should avoid wearing tight clothes and to keep a “clean heart” to stave off the influenza.

At first, Sharpley and other officials didn’t believe the emerging flu cases were related to the deadly outbreak that was reportedly making its way across America. But by the time they realized they were facing the epidemic, Denver hospitals were already seeing their first Spanish Flu patients, and the virus was swiftly spreading throughout Colorado.

According to an article on how Colorado reacted to the Spanish Flu published by the Colorado Sun, local leaders banned public gatherings and implemented quarantine measures, but the unevenness of their enforcement and implementation wore down the public’s trust and confidence.

“At various points, citizens were required to wear masks in theaters and shops, but not churches and hotels. Restaurant waiters had to wear them. Diners did not.”

In a direct parallel with how COVID-19 impacted America in recent years, clashes and concessions made between politicians, public health officials, and business leaders gave the Spanish Flu opportunities to spread throughout the state uninhibited. And similar to how throngs of young adults flocked to south Florida for spring break despite warnings that they’d contract or unknowingly spread the novel coronavirus, Colorado socialites continued to defiantly gather for parties during the Spanish Flu outbreak.

Some Denver leaders largely believed the sickness could only be spread indoors, and large groups were legally permitted to gather outside, a decision that unwittingly aided the virus’ transmission. When cases continued to rise, Sharpley eventually banned outdoor gatherings and made attending one a criminal offense.

Efforts to contain the virus in Colorado ramped up throughout the fall until the official end of the First World War on November 11th, when millions of Americans celebrated out in the streets. By then, reported cases had begun to slow, and many believed the threat from the lethal flu was gone. Outdoor gatherings on Armistice Day led to a resurgence in the deadly flu that ravaged large swaths of the country, particularly in Philadelphia and other densely populated areas along the East Coast.

However, Denver was largely spared from this trend, and restrictions in the city were slowly lifted, and churches, theaters, and local businesses began cautiously opening their doors again. Flu-related deaths began to wain in the capital, but other parts of Colorado continued to be devastated by the Spanish Flu in November and throughout the fall, winter, and spring.

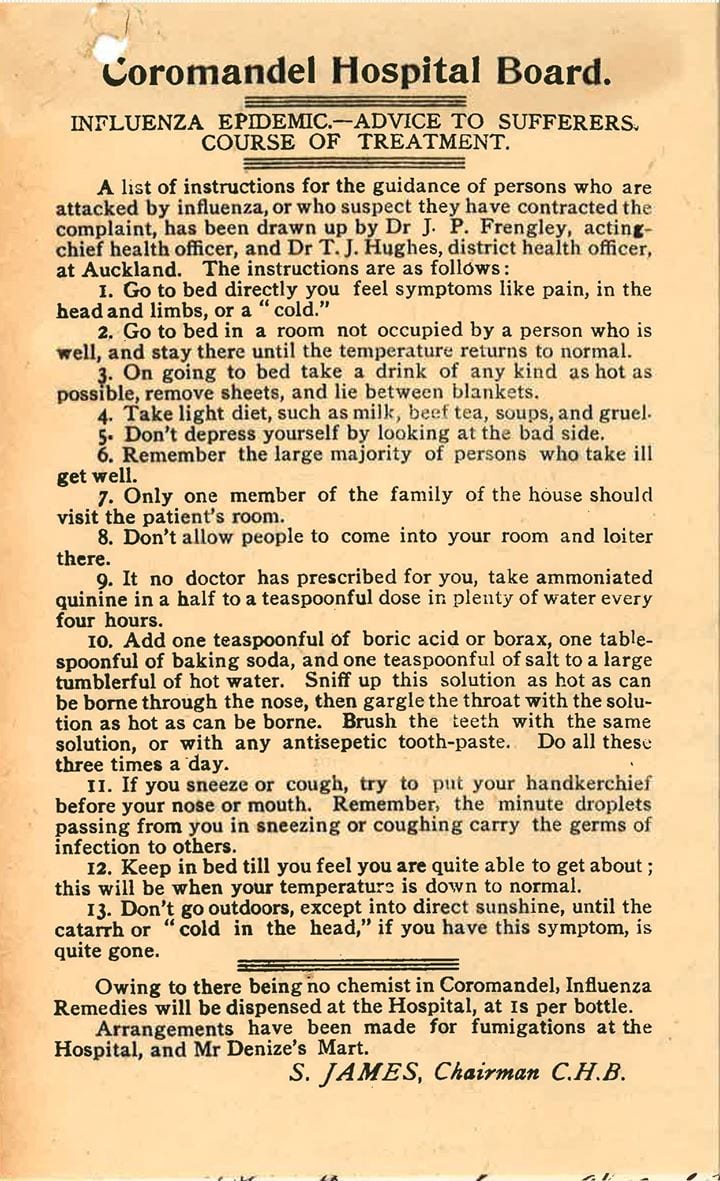

The city of Pueblo tried vaccinating its steel workers, and the Mayo Clinic inoculated patients in Greeley and Montrose, but nothing proved to be effective. We now recognize the Spanish Flu to be caused by a viral infection, but many doctors at the time believed that bacteria was to blame during the pandemic. Countless victims held out hope for a vaccine, but history shows us that health experts of the era were nowhere close to developing one.

Today, Colorado is thought of as one of America’s hardest-hit states from the Spanish Flu. Out of the states that tallied deaths from the virus, Colorado’s flu-related fatalities reached nearly 8,000. According to history professor Stephen Leonard, that would be the equivalent of 37,000 Coloradans dying from the Coronavirus over four months with the state’s current population.

Native American communities in Colorado were especially impacted, and 3,293 registered deaths were recorded in the Four Corners area alone. In Colorado and throughout the United States, healthcare systems were stretched to their breaking points, and a destructive anti-immigrant sentiment took hold.

Gunnison and the Spanish Flu

However, one Colorado area is widely looked to today as a model for evading lethal pandemics. The community of Gunnison was so famously adept at dodging the lethal impact of the Spanish Flu, that the U.S. Defense Threat Reduction Agency has studied their methods and sought to use them to protect American troops.

Gunnison reacted strictly and urgently to warnings of the pandemic, closing schools and banning gatherings from the onset of the earliest statewide warning.

The local paper documented the plight of Salida, Sargents, and other surrounding communities that were rumored to be ravaged by the pandemic, and locals paid attention. Travel was heavily monitored and restricted throughout the county, and residents were permitted to leave but couldn’t return without being quarantined. Checkpoints materialized on main rail and roadways and police officers informed vehicles that if they stopped anywhere in the county, they’d be swiftly quarantined. Travelers who tried to evade the checkpoints were jailed.

While Gunnison’s remarkable safeguards undoubtedly helped protect the community, research has discovered that luck was a major factor that helped protect the community. By the time Gunnison was first warned about the pandemic, it was already spreading throughout Colorado’s mountain towns, and residents of those areas who worked in mines and had respiratory problems were especially impacted.

The Spanish Flu did eventually make its way into the area, but long after it appeared in nearby communities and in a far less severe way. A combination of luck and vigilance saved Gunnison from the worst of Spanish Flu, and made the area a place we still look to today to protect ourselves from pandemics.

By heeding warnings and thoroughly enforcing them, Gunnison went down in history as a community that was able to blunt the vicious blow the Spanish Flu had dealt the world, but they didn’t evade tragedy completely. In November of 1918, two sisters who’d returned from a trip to Chicago became infected, and one died. News of the death quickly made its way throughout the county, and residents responded by increasing their adherence to local restrictions.

Four months later, local officials lifted bans on gatherings and once again allowed cars and trains to pass through the county freely. Tragically, a third wave of flu struck Gunnison a month later, infecting 100 and killing 5.

The way different Colorado communities faced the Spanish Flu is an important part of history.

How to Ride the A Line, aka Denver Airport Train

How to Ride the A Line, aka Denver Airport Train