You might not realize it, but most large bodies of water in Colorado are dammed-up manmade reservoirs and not natural lakes. Like the rest of the American West, Colorado is quite dry and is trending even dryer because of the impacts of climate change.

According to a Denver Post article published in August 2020, 100% of the state is currently either suffering from drought or “abnormally dry” conditions. Colorado’s many large dams plug up rivers to store drinking water for dry times such as these, and many also provide renewable energy for the state and prevent flooding.

However, it should be noted that these dams come at a steep cost to Colorado’s environment. From wreaking havoc on local fish populations to creating “dead zones” in rivers that can’t support life of any kind, dams are proven to take a serious toll on the riparian environments they’re built.

Today, we’re taking a closer look at Colorado’s most notable dams and the stories that come along with them, from the unbelievable relocation of an unlucky mountain town to make way for a reservoir to a transformational natural event that created one of the state’s largest natural bodies of water.

Grand Valley Diversion Dam

Listed on the National Register of Historic Places, the Grand Valley Diversion Dam was constructed from 1913 to 1916 and is located northeast of Grand Junction on the Colorado River. One of the first and largest dams of its kind to be constructed in the US, the Grand Valley Diversion Dam is a Roller Dam consisting of six gates, which were designed to reduce erosion and divert irrigation water to the surrounding areas.

In the 1930s a hydroelectric power plant was added to the historic dam as well. The fact that this dam is still in use today shows the ingenuity and timelessness of its design.

Dillon Dam

As far as towns go, Dillon has had a rough go of it throughout its 140-year history. Wedged between the Dillon Reservoir and 1-70, today the tiny community of Dillon might not look like much more than a couple of chain restaurants and a few modest local businesses, but it has quite a story to tell.

Established by ambitious prospectors along the Snake River in Summit County, Dillon was incorporated in 1883. But almost as soon as it was founded, Dillon had to pick up and move to the west bank of the Blue River because the Denver and Rio Grande Railroad skipped servicing their tiny town. It was moved again, not even a decade later, to gain closer access to the Denver, South Park, and Pacific Railroad.

Dillon residents had barely settled into the town’s new location by the time Denver leaders started mulling over plans to transform the surrounding area into a massive freshwater reservoir. When locals couldn’t pay their property taxes during the Great Depression, the Denver Water Board snatched up the land they needed to begin work on the project and notified residents that they’d need to leave or vacate their homes by 1961.

Construction began soon after and was completed two years later. Since businesses and households were required to entirely shoulder the burden of relocating structures themselves, most understandably chose not to. However, the structures that were moved stand today as historic symbols of tenacity.

The Dillon Community Church, Town Hall, and Arapaho Café and Motel were moved in the early 60s and are still operational today. Now known as the Mint Steakhouse, the Mint Bar’s move to nearby Silverthorne was just one of three relocations the iconic building underwent after being constructed in 1862.

Blue Mesa Dam

When it comes to the largest reservoir in Colorado, the Navajo Reservoir holds the title, but with one big caveat: Most of it is in New Mexico, not Colorado. This brings us to the Blue Mesa Reservoir, which at 9,180 acres, comes in at an impressive second place. To hold this astounding amount of water, the Gunnison River was plugged west of town with a behemoth 390-foot-tall dam.

Constructed in 1966 by the Bureau of Reclamation, the dam generates hydroelectric power, prevents flooding in the local area, and stores fresh water. It’s also the largest Lake Trout and Kokanee Salmon fishery in the state as well as a beloved scenic outdoor recreational area managed as part of the Curecanti National Recreation Area under the National Parks Service. The area has become popular for camping, fishing, boating, and hiking.

Lake San Cristobal

Unlike the rest of the dams highlighted on this list, the one responsible for forming Lake San Cristobal wasn’t made by human hands. Located deep in the Rio Grande National Forest, Lake San Cristobal is generally considered to be one of the most breathtaking natural areas in the state, and its origin story perfectly suits the grandiose drama of its landscape.

The dam was formed 700 years ago when a natural landslide called the Slumgullion Earthflow blocked Lake Fork, a tributary of the Gunnison River. Natural dams like this one can be found around the world, but they typically fail after a relatively short period. However, the natural dam at Lake San Cristobal isn’t like other dams.

The United States Geological Survey found that the dam’s natural spillway was firmly cut into bedrock, which makes it stable. But if you want to see this remarkable natural dam for yourself, your time is limited, sort of. Sediment sourced from local creeks flowing into the dam is slowly filling up the reservoir, according to experts, and the whole thing will be packed entirely with natural debris within 2,500 years or so.

Cherry Creek Dam

Southeast of Denver sits a favorite outdoor recreation spot for locals, the Cherry Creek Reservoir. You’d assume that this 880-acre body of water is to store fresh drinking water for the ever-expanding Front Range population, but that’s not the case. According to the US Army Corps of Engineers, the Cherry Creek Dam is just one of three dams in the area constructed to

“lower the risks to the Denver region from catastrophic South Platte River floodwaters that have plagued the area for more than 100 years.”

Built at the confluence of the Cherry and Cottonwood Creeks, the dam’s slipway is designed to divert floodwaters away from local structures and has never been used. But even so, the dam is seen as a notable risk because of the densely populated areas that surround it.

A weather event dropping twice as much rainfall as the storm that soaked Boulder County in 2013 would need to occur for water to spill over the dam, according to the US Army Corps of Engineers. But if you live nearby, you shouldn’t be too worried because the dam’s creators estimate the chances of that happening are a scant one in 58,800 during any given year.

Chatfield Dam

Another dam created to mitigate flood risks in the Denver metro area, the Chatfield Dam is located south of the Denver suburb of Littleton. Weighing in at 1,500 acres of surface water, this massive engineering project took eight years and 74 million dollars to complete (that figure is equivalent to over 358 million dollars today).

In addition to preventing local flooding, the area has become a popular outdoor recreational staple for the suburbs southwest of Denver and offers horseback riding, boating, fishing, and many other activities. In 2017, a project was launched to add over 20,000 acres of water to the reservoir, which will raise water levels by 12 feet upon completion.

To accommodate the sweeping change, some of the existing structures at Chatfield State Park are being pushed further up the shoreline and away from the expanding water levels.

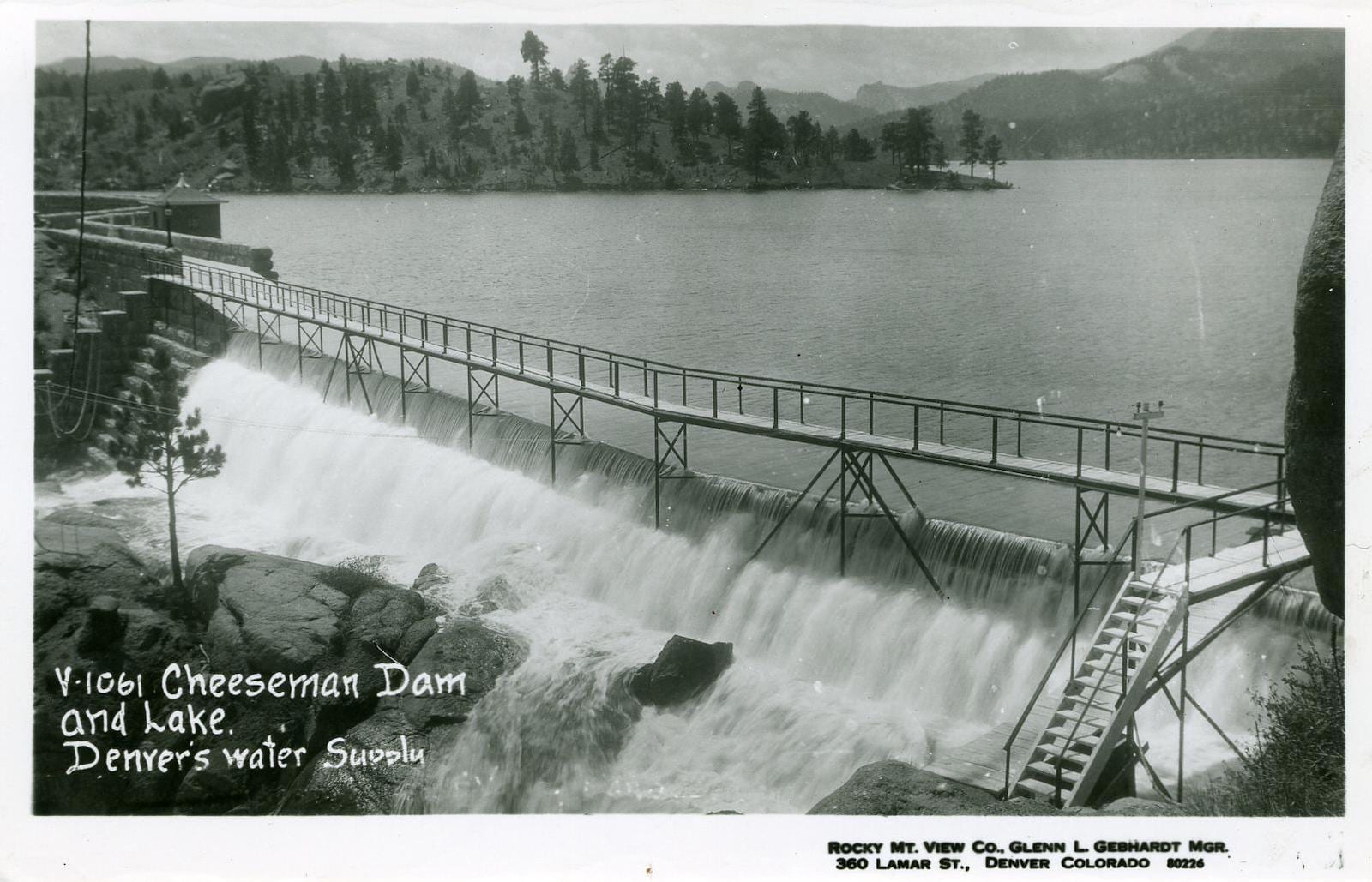

Cheesman Dam

Located at the bottom tip of the Jefferson County boundary, the Cheesman Dam was constructed in 1905. At the time of its construction, it was the largest masonry curved gravity dam in the world, and it put Colorado on the engineering map.

Named after Colorado businessman Walter Scott Cheesman, Cheesman Dam was designated a Historic Civil Engineering Landmark in 1973. This dam blocks the South Platte River and is used for freshwater storage. You can enjoy recreation in the resulting Cheesman Lake.

Colorado features thousands of named bodies of water, some natural, some manmade. Here’s a list of the lakes and reservoirs in Colorado for you to explore further.

Top Things To Do in Estes Park, Colorado

Top Things To Do in Estes Park, Colorado